I’ve written about a couple of example cases and explained how onboarding bandaids often don’t work. Time to dive into the top of the marketing funnel.

Identify the Right Problem

I love challenging assumptions, so when I am told there is a problem and the cause is “that part”, I always take a step back and consider the system. As I wrote in part 2, many folks thought we had a problem with the social platform’s homepage since so many new users did not return. Since the homepage was something each of their experiences had in common, you can see how the conclusion makes sense.

However, we had little insight beyond web analytics. I did what I always do to understand what’s going on with underperforming products – I conducted user research in the form of a usability test. One testing approach would have focused on the homepage and I could have designed a test that only showed participants the homepage and evaluated how well it communicated the site’s purpose, or how easy it was to navigate, or determined new users’ initial actions, or other things. However, no one shows up at the homepage without signing up and no one signs up without first loading our landing page and they don’t get there without responding to an email or mailing from one of our partners.

All of that context is crucial to setting up the study to answer the question: Why are new users not engaging?

So, how do you communicate that context? You recruit representative users and have them experience all those steps themselves. When they reach the homepage, they will have the same knowledge and context as the people you hope to better understand.

The Problem

As I wrote earlier, it was quickly obvious that the initial messaging was confusing and misleading. The biggest problem was terminology which is not too surprising when you consider an audience from across the country with varying backgrounds.

Here’s just one example of many: The platform offered discussion forums – topic-based areas where members could post messages and comment on those messages. However, the initial email and landing page simply called these “groups”. Some participants thought these were membership-based clubs that met on a regular schedule and required a level of commitment and some even extrapolated from there to assume groups only met in-person.

This and other miscommunications affected participants differently. Some became interested in things the platform didn’t offer. Some became less engaged due to a misunderstanding. Others would have been more engaged had they properly understood. We even found that a strong emphasis on “making friends” had a surprisingly negative effect on many people we interviewed. So, viewing the homepage with these varied understandings was quite different than landing there without preconceptions. Assumptions and first impressions had been formed and they affected behavior.

Even though the stated goal for improving the homepage and onboarding was increasing engagement, I don’t think we could meaningfully do that without tackling this problem first. We really needed to reduce the number of variables we were designing for. Without upstream changes, we’d have to tackle these misunderstandings first in the product as part of onboarding.

This is why aligning marketing, business development, and product was the first priority. Even our small company had built silos that needed to be breached.

Fixing the Funnel

Our testing and research helped us better understand members’ priorities and the language they naturally used for the concepts we offered. Identifying the problem also gave us a wealth of knowledge we could use in designing the solution and, later, improving the homepage and the platform as a whole.

We shared our findings with the entire company, sharing test video to really prove the point. That got everyone on board to work on solving the problem.

With a clearly defined problem, design follows easily.

Our design team worked collaboratively with other teams to iteratively redesign the marketing messaging and landing page. We improved and aligned terminology, we added adjectives to clearly communicate concepts, and we made sure to reflect the user priorities we heard in our research. We kept testing, too, and could see the improvement after each iteration.

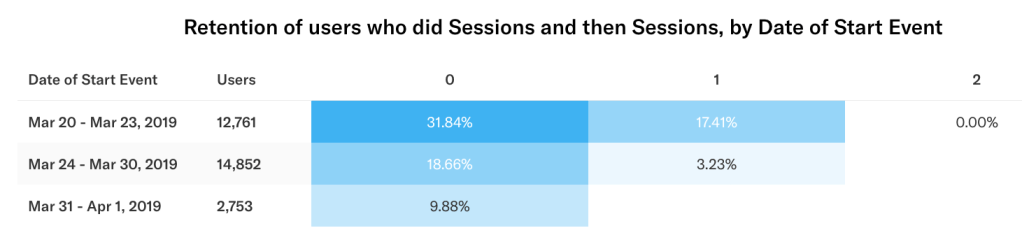

After the next major release, we found these design changes doubled the conversion rate.

It was a successful project and not at all what stakeholders thought they were asking for.

Thanks for reading. Stay tuned for the final part of the series where I discuss addressing core design problems affecting a released product.

My previous post was about balancing problem definition against design and implementation. The balancing act doesn’t end there, though. Even after defining the problem, there are usually multiple solutions to choose from and each of those can be considered complete with varying levels of functionality.

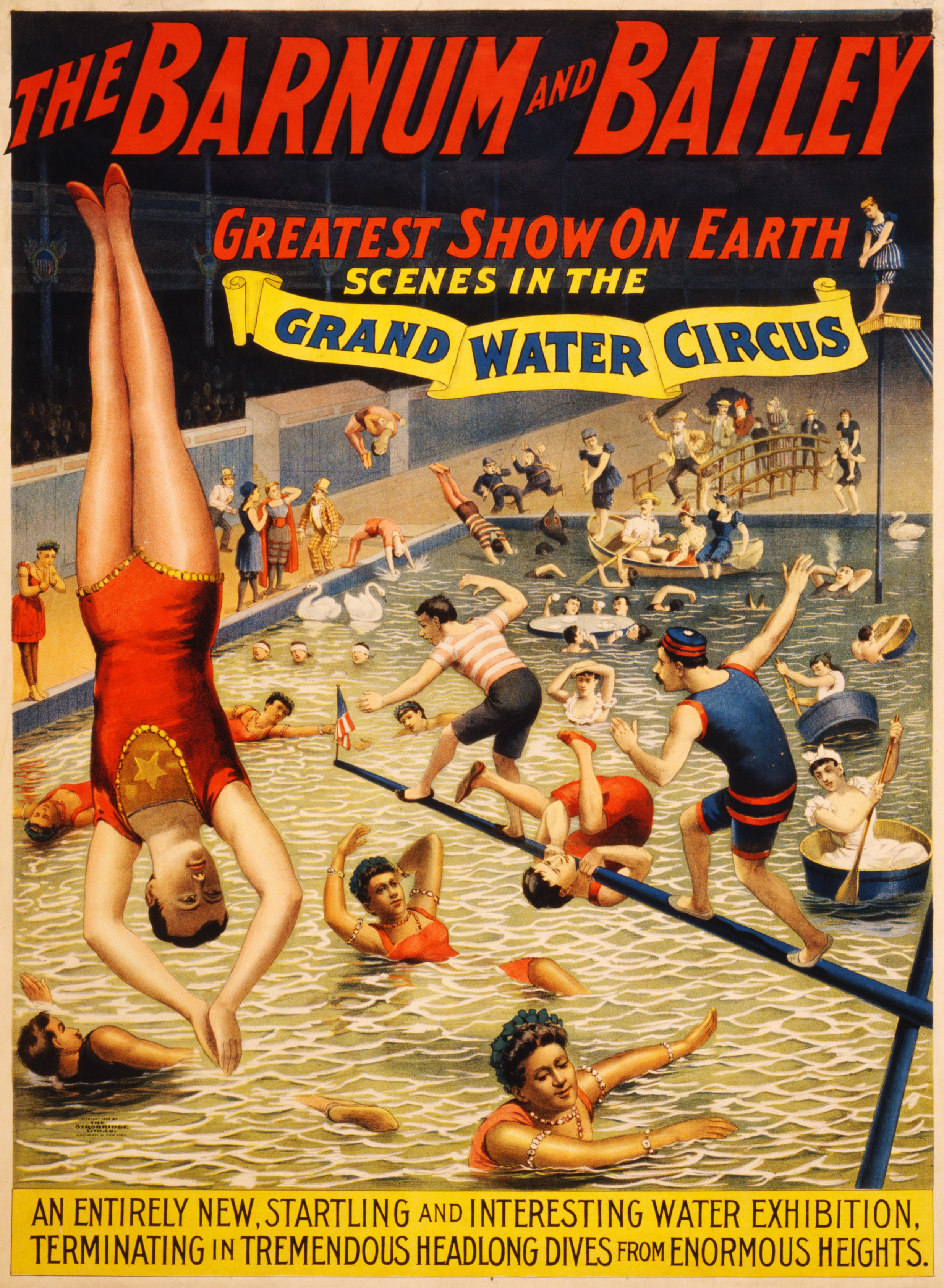

My previous post was about balancing problem definition against design and implementation. The balancing act doesn’t end there, though. Even after defining the problem, there are usually multiple solutions to choose from and each of those can be considered complete with varying levels of functionality. The performer finds balance through feedback, practice, and experience. Designers achieve balance the same way. The tightrope walker knows when they’ve fallen off the tight rope but it’s harder to know when a design is off balance.

The performer finds balance through feedback, practice, and experience. Designers achieve balance the same way. The tightrope walker knows when they’ve fallen off the tight rope but it’s harder to know when a design is off balance. Does your work ever feel like a circus? Yeah, mine too. I feel like I am always performing. My most popular performance is the balancing act – it turns out that product design is a series of balancing acts.

Does your work ever feel like a circus? Yeah, mine too. I feel like I am always performing. My most popular performance is the balancing act – it turns out that product design is a series of balancing acts.