This is part 3 of my blog series on onboarding and retention.

When new users struggle with a product, there are a few quick fixes teams often try. They are simple, cheap (sometimes), and have low product impact (there is little code needed). I’ll take a look at a few and point out some gotchas.

More Explanation

A common fix is to throw more information at the user.

The explanations come in many forms:

- Additional documentation, maybe with links embedded in various parts of the application

- Blocks of explanatory text embedded on the app pages (in-product documentation)

- Marketing email campaigns

- Outreach from customer support to help users one-on-one

These are pretty blunt instruments. They rely on your users reading or watching additional content. It’s a common refrain that “people don’t read” and that is often true. It’s especially true if the person is not motivated to do it. In trial or try out cases, the user is often looking to see how your product is going to help them, not read more about it.

In addition, these approaches have other drawbacks. In-product documentation engagement is hard to measure. Marketing emails are generally better at getting people back into the product than explaining concepts. Customer support is likely effective if they reach a user but is a very expensive and non-scalable solution.

Finally, in-product and standalone documentation are pretty static. If you’re not careful, you will end up with blocks of text that, once read, provide zero to negative value. Or, you will introduce a ton of documentation that few people read and must be maintained which, for a quickly evolving product, is not an easy task.

Tooltips, Product Tours, “In-App Experiences”

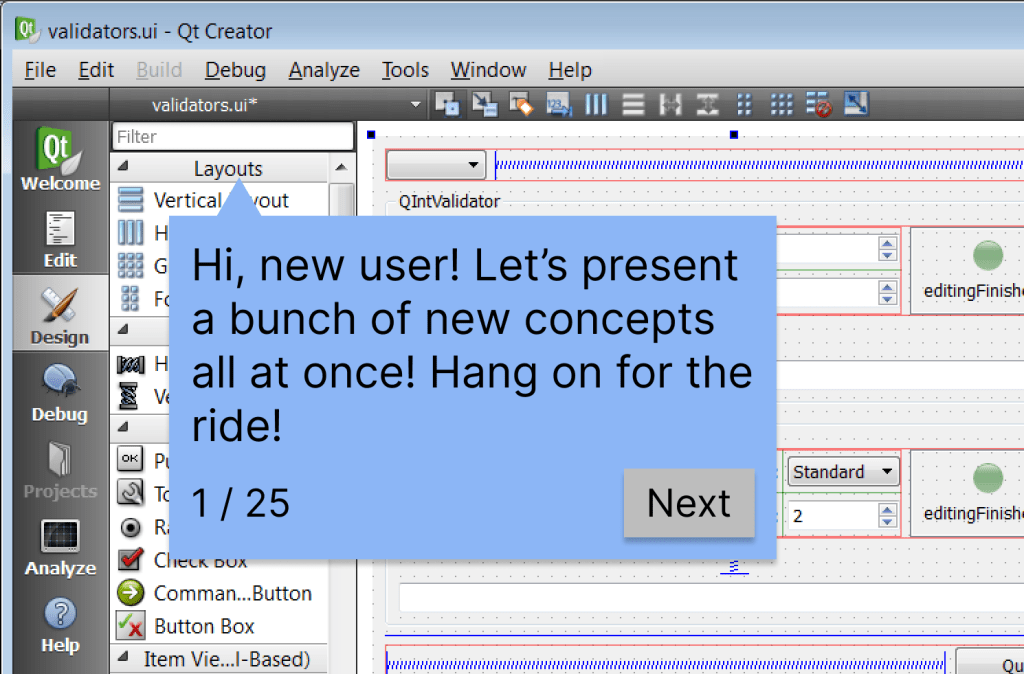

I am sure you’ve experienced the tooltip onboarding aid. Your first visit to an app pops up a number of small, helpful tips that point things out on-screen or guide you through one or more tasks. There’s no doubt these can be helpful and multiple companies have built tool businesses around this pattern.

The many 3rd party products are easy to integrate into applications and, better yet, enable anyone outside the engineering team to author and maintain the tooltips. However, authors need to take care that their tooltips and flows are well-tested and understand that every app update risks breaking them. The tooltip triggers and positioning often rely on HTML and CSS details that, if poorly understood, can result in surprising behavior. Poorly engineered front-end markup can also make for brittle tooltips.

Another weakness I’ve seen with these tools (though, perhaps someone has addressed this) is that it is very difficult to support guided flows across multiple page and state changes. For example, the tooltip logic might rely on a list containing only a single item and will only work the first time a user does the associated task. Or you may want tooltips to appear only if the application is in a certain state but that data is not available to the tooltip logic. These constraints force the author to only provide guidance in specific, limited contexts.

While each tool has its own technical strengths and weaknesses, the pitfalls to avoid are universal. Here are a few:

- Obvious explanations – Try to avoid tooltips that explain obvious concepts or operations. Is it really necessary to point out the logout button with a note saying it logs you out? Maybe in some cases, but error on the side of brevity.

- Excessive explanations – The social platform I described in part 2 had over 20 tooltips, displayed one at a time, that explained every button and section of the app’s home page. Torture. When we conducted usability testing, we found the homepage and main navigation was understandable and those tooltips were unnecessary.

- Bad timing – Timing is everything. Someone learning a new application will simply not absorb information that is provided at the wrong time or in the wrong context. For example, if you need to explain how to schedule a new blog post, don’t explain it when I create a new, empty post (or worse, right after I’ve created my account!). A better time would be when I save a draft or attempt to publish a post.

- Forced flows – Some guided flows take control away from the user, likely to avoid having the flow disrupted by an errant click or a bored user. Some force users down irrelevant (to them) paths. The social platform I worked on had at least a couple of distinct personas. If a new member, uninterested in social interactions, was forced down a guided tour about online chats and discussions, they may abandon the product. If the user is not engaged, they are unlikely to learn or remember these.

- Poor explanations – Sometimes a product using unfamiliar jargon or concepts is a design deficiency you need to bandaid. If the author is unaware, the help can continue obfuscating things. Instead, treat the tooltips as an opportunity to help new users translate familiar concepts and terms into the application’s world. Be sure to write tips in the user’s language, even if that departs from marketing, branding, and product jargon.

This type of help is not a magic bullet. To be successful, you need to do the work to understand where and when your users need help and apply it sparingly.

As a matter of fact, the work needed to design in-product help is a lot like the work needed to design a product… Hmm… 🤔

Helping People

For new users to your product, your goal is to make them proficient users of the product. For many products, these people will need to learn something. Jared Spool has a nice analogy describing this learning destination as “target knowledge”. Your goal is to get them from their current knowledge to this target knowledge. Ideally, you can do this as an implicit part of the product design by doing your research and designing it in.

- Know your users. Understand their starting knowledge, behaviors, and goals.

- Design for new and experienced users. I will touch on this more in part 5 where refactoring the design to better support new users actually helped existing users as much or more.

- Introduce concepts incrementally if you can. Provide help (in whatever form) when the user needs it.

You may still find areas where guides and other bandaids are needed but I bet you will be able to deploy them with precision and confidence.

Wrap Up

Like any product, feature, document, or anything with an audience, you need to do your research to understand how your users think, what their goals are, and what expectations and knowledge they come to you with. Without that work, even though these fixes don’t heavily impact the existing product, these aids will fail to help.

In parts 4 and 5, we’ll look at the cases I described in part 2. Both these examples illustrate cases where bandaids like these made little impact.